Earlier this week, I was sitting down in front of the TV doing some research for this blog. Some of you may be wondering how the idle ramblings of a skater in his mid-twenties with a bum ankle could in any way necessitate research. Research is often equated with the idle shuffling through google, or occasionally through a book (editor's note: books are things, kids - google them for yourself), the kind of shuffling that often leaves one borderline catatonic and in need of some manner of mental stimulation. How, then, you might ask, can you claim that the immersion of the mind in all things skateboarding can in any way come close to research?

Well, for one thing, readers into whose mouths I just shoved words, research does not always equal boredom. I spent years researching ancient and not-so-ancient history, and from time to time the material was engaging, and even exciting to sift through. For another thing, the research subject in which I was about to imbibe was in no way something to be looked forward to.

As a bit of a preempt, I suppose I ought to explain why I was about to subject myself to something that was, by all rights, an ungodly mess. Skateboarding tends to grab people in various different ways, shapes, and forms. Some people relish the simple act of skateboarding itself. Some live and die by whatever hot new trends are coming down the pike via magazines, videos, and the internet. Few people have want or need for the decades of triviality that have accompanied the activity since its inception. I happen to be one of those few.

Perhaps it stems from my early adolescent equation of "the more you know about skating, the more you are a 'real' skater", or from the years of studying history. Maybe it just boils down to the fact that I've always been a big nerd. Whatever the reason, I seem to have this deep compulsion to expose myself to anything that involves skateboarding in even the slightest amount, the good, the bad, and the inevitably ugly. With that being said, consider this a new monthly feature on top of "Skateboarding Is...", where I'll look at one thing that has fallen into each of these categories for me in the last month.

The Good: Go Skateboarding Day 2011

This one seems like it ought to be obvious, like I ought to be talking about something else: The one day of the year that is dedicated to skateboarding and skateboarders (at least in our own minds). If you could skate, I hope you did.

There is more to my mentioning the now annual event, however. This week, as the annual pile of GSD footage came rolling in from this company and that, I noticed a greater-than-ever geographical breadth to it. Among the most notable was an edit from Tehran, Iran, as well as news of NPO and overall third-world do-gooders Skateistan holding events for the first time in Phnom Phen, Cambodia. Footage like this not only warms the heart with the knowledge that even the youth of war-torn and destitute locations can find solace in skating, but it also reminds those of us lucky enough to live in G8 nations just how lucky we are. Not to sound preachy, but I have a seven-inch long piece of titanium holding my fibula in place after Humpty-Dumptying the thing at an exquisitely built concrete park, and all I paid for was the cast and some pain killers. You can bet the next time I'm even skating a curb that I'll be trying to enjoy it half as much as the skaters of the third world.

The Bad: Free Pegasus

Okay, now that I had my moment on the soap box, time to be critical. I can remember watching Brian Lotti's first foray into the fly on the wall street mockumentary, 1st and Hope, and loving it. The whole thing was beautifully orchestrated, with a genuine tone, and cinematography that made it seem like you were actually witnessing a day in the lives of a bunch of skaters in Los Angeles. To this day, I watch it and it gets me stoked to go out in the streets and just skate.

On paper, Free Pegasus seems like another winner: the same basic formula, but set in international skate mecca Barcelona. I was genuinely excited to see the two protagonists were Clint Peterson and Cooper Wilt, but that was, for the most part, where the excitement ended. Don't get me wrong, the skating in the video was good, really good in spite of the relatively sparse number of notables in the cast. The real reason Free Pegasus fell flat was that it simply felt too forced. There was far more dialogue in this offering, as well as the introduction of sub-plots, and supporting characters that didn't skate. Any realism that Lotti managed to convey in 1st and Hope was lost in a sea of foreign film-esque character development, sub-par acting on the part of the skaters, and one very out-of-place Clint Peterson fisheye line at MACBA. While I do Hope Brian Lotti tries another one of these types of videos, I hope he does so with a return to form.

The Ugly: Disney XD's Zeke and Luther

When I had mentioned my research earlier, this was the abomination to which I was referring. Anyone who has a sibling or relative who was born after 1991 has probably had some kind of exposure to the plainly awful stuff that is Disney pre-teen sitcoms. Poorly written, poorly acted, poorly executed. The only thing that could possibly make them any worse? The obligatory wrenching in of skateboarding as a plot device. It's interesting to look at from a purely anthropological perspective, like reading Lord of the Flies, but more depressing.

The particular episode I had subjected myself to involved the titular characters (hereto known as straight kid and goofball), getting ready to celebrate their tenth anniversary of skating with a big party at the local doughnut shoppe (not actually spelled that way, just thought it might be amusing). Whilst reminiscing about the day when a random translucent green skateboard showed up in front of them, therein sealing our protagonists' destiny, it is revealed that footage exists of the event. Upon watching said footage, it is revealed that (le GASP) goofball rode the skateboard before straight kid, upsetting both their collective memory of the event, as well as their obvious hierarchy. The revelation leads to goofball declaring that during their next session, he would be "lead boarder", and the inevitable hijinx ensue. I won't bother boring you with the rest, as I've probably lost a good deal of my readership with the last paragraph alone. I can understand the desire to market skateboarding to youth, notably the "tween" crowd, but come on, Disney, you're better than that. Take a cue from Nickelodeon, and get Skate Master Tate on the phone.

Thursday, 30 June 2011

Monday, 27 June 2011

The Spacewalking Dead, or An Ode to the Approaching Freestyle Apocalypse

North America: in spite of half of the continent being founded on the want of freedom of choice and a puritanical value set, said continent is, on a whole, more or less the global bastion of conformity and decadence. Skateboarders have always prided themselves in their countercultural spirit, with countless skaters rejecting the status quo, dressing different than the preppy, popular jocks at their high school, or being content to live in squalor as long as they have their skateboard. Clearly the skateboarding population of North America is a shining example of all the good things that all the unwatched masses within the allegorical cave are not.

The above is a paragraph that I wish I could have typed out with a straight face and lack of ironic sarcasm.

I love skateboarding, I love my country (the one to the north, whose colonization was based less on religious freedom and more on making a quick buck off beaver pelts... funny thing, that role-reversal), and I will admit, as I just did, that the continent on a whole revolves around following trends and living in excess. That being said, I cannot help but humbly disagree with all the adolescent ideologues out there who believe that North American skaters are any different than anyone else on this particular landmass in either respect. How else might one explain the fact that, for decades, skaters who didn't dress "like skaters" were branded as posers? This trend seems to have finally dissipated, though, as the entire world's youth now dress "like skaters", diving into either their local Hot Topic or Hip Hop surplus and crawling out three hundred dollars later with outfits that look like they cost twenty five bucks at a goodwill. Further, if popular skateboarding isn't full of excess and trendiness, than how does one explain how modern street skating has divulged into either a game of chicken with one's own kneecaps, or an exercise in cramming as many maneuvers onto a single ledge as humanly possible? I'm all for progression, but this is ridiculous.

Skateboarders on this side of the pond are, by and large, just as trend-conscious and excessive as all the other sheeple they so adamantly claim to reject. This is why Vertical and Freestyle died as soon as the big ball dropped in Times Square in 1990. At least, this is why they died, in North America.

If nothing else, Europeans can claim that their value of art is far superior to any and every North American. It's not surprising, then, that it was in Europe that Freestyle managed to stay stable, albeit still on life support. While it took until the year 2002 for Freestyle skating to again see the light of day over here, it seems to have been largely relegated to a passing affection; thirteen-year-olds learning some "Rodney Mullen tricks" to best their friends in games of S-K-A-T-E until their legs grow strong enough for them to learn frontside flips. In Europe, however, Freestyle maneuvers were nurtured and cultivated. Contests were held, videos were made, and pros released models. It would seem that, in North America, Freestyle was cast aside, except for the parts that could be used to throw oneself down a flight of stairs, deemed as useless for lack of an ability to fuel North American skaters' addictions for excessive speed, while in Europe, the skill and artistry of freestyle was nurtured as just that. It is for reasons like this that it was Spain, and not the united States, that gave the world Kilian Martin.

I had watched Kilian's videos several months back, and was plainly amazed by them, but it was not until recently, when a friend favourited A Skate Regeneration on her youtube page that the thought occured to me to say anything about him. The above mentioned, and shared, video seems a perfect example of an avenue of skateboarding that has been ill-examined. In a world where Aaron Homoki is launching himself down two-story drops and Tory Pudwill seems content doing no less than two different grind variations at once, the question that is posed more often than ever is "where do we go from here?". Kilian Martin's admittedly unique brand of skateboarding acts as a welcome answer to this quandary. In the smattering of footage that the twenty-four year old Madrid native has shared one can see a world of opportunities for any street skater with a good sense of balance, an open mind, and undoubtedly a world of patience.

To all the skaters out there reading this blog: the next time you're out street skating, and you find yourself at an impasse in terms of what to try next, pull out your undoubtedly internet-ready phone and find some old freestyle parts. I mean, it worked for the Gonz, right?

The above is a paragraph that I wish I could have typed out with a straight face and lack of ironic sarcasm.

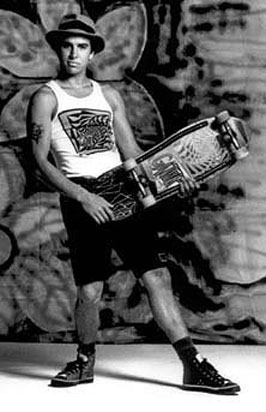

| |

| Dressing "Like a Skater" circa 1987: I'm pretty sure murder will brand you and instant "poser" |

|

| Dressing "Like a Skater" circa 2008: Do you think she watched the Pool Party? |

Skateboarders on this side of the pond are, by and large, just as trend-conscious and excessive as all the other sheeple they so adamantly claim to reject. This is why Vertical and Freestyle died as soon as the big ball dropped in Times Square in 1990. At least, this is why they died, in North America.

|

| Above: A Rodney Mullen Trick |

I had watched Kilian's videos several months back, and was plainly amazed by them, but it was not until recently, when a friend favourited A Skate Regeneration on her youtube page that the thought occured to me to say anything about him. The above mentioned, and shared, video seems a perfect example of an avenue of skateboarding that has been ill-examined. In a world where Aaron Homoki is launching himself down two-story drops and Tory Pudwill seems content doing no less than two different grind variations at once, the question that is posed more often than ever is "where do we go from here?". Kilian Martin's admittedly unique brand of skateboarding acts as a welcome answer to this quandary. In the smattering of footage that the twenty-four year old Madrid native has shared one can see a world of opportunities for any street skater with a good sense of balance, an open mind, and undoubtedly a world of patience.

|

| Parting Shot: Gonz doing a Rodney Mullen Trick |

Thursday, 23 June 2011

Sometimes I Prefer 1000 Words, or The Art of a Good Dialogue

To start, it is an unfortunate duty of mine to have to pass along the news of the recent passing both of Thrasher Magazine and Independent Trucks co-founder Eric Swenson, and Jackass alum Ryan Dunn. Both of these men's lives were cut short by truly tragic means, and my thoughts and sympathies go out to grieving friends and family.

On a slightly happier note, today marks the day I get my cast off. It's been a surprisingly fast-moving seven weeks, and I had considered writing a sort of survival guide for anyone laid up with a bad break, except that there is little to know, except for the fact that you will do little more than watch web shows and gain a few extra pounds, so good luck to anyone in a similar situation. I know I'm still a ways off from actually skating again, much less at the level I was before my break, but I will toss out the occasional update as per my status.

To be perfectly honest, I had no idea when I started this post what exactly I planned on writing about. Typically, ideas for this blog come from my glancing a handful of skate news websites, maybe watching something that catches my eye, or a discussion with someone, with any of the three somehow going through a series of filters in my head, eventually leading me to some kind of conclusion I wish to ramble about that Monday or Thursday. This week, there was little to work with, or at least, little that my mind was able to form any kind of thoughts about that would carry for longer than maybe a paragraph. For instance, Go Skateboarding Day came and went on Tuesday... most skated, I didn't (for obvious reasons), end of story. As far as skate news, there didn't seem to be much to go on; perhaps it was the two months of not buying either Thrasher or Transworld, or the fact that there were no recent videos that really caught my eye...

...Alright, so the part about the videos isn't exactly true. In fact, in the last week I came across two videos that very much piqued my interest. So why then, you are likely asking, am I not blogging about said videos? Well, for one, I haven't given myself the time to watch them both in their entirety, and two, they are both interview-heavy skate documentaries.

As I find myself growing older, I can't help but note that creeping sense of disconnect between myself and the pulse of popular skating. Yes, I do make an effort to try and buy skate magazines every month, and yes I do peruse my handful of skate news sites daily, but the reality of the situation is that while, yes, the act of skateboarding may be the closest thing to the fountain of youth, even skateboarders mature to some degree. That being said, while I do still enjoy reading skate magazines and watching skate videos, it has gotten substantially harder to relate to the up-and-coming new-jacks of the industry; sixteen year old handrail hellions who, when interviewed, seem to have trouble using multisyllabic words, much less saying anything meaningful or engaging.

I can't be too hard on these kids, though. They're young, they lack life experience, and while it pains me to say it, most of them care little for being educated. The truth is, as a university alum and an older skater in general, I require substance in my reading and viewing material, and flipping through a series of six page interviews with maybe five hundred words of text simply feels sub-par.

Maybe it's my age, or maybe it's the fact that you can only read the same interviews and watch the same video parts so many times in one decade, but the important thing is that I, we, live in a day and age with choices. For so many years skateboard media was run by skaters, and skaters were kids; no one over twenty-five skated, because skating hadn't been around long enough. These days, the kids who ran the skate media of yesteryear have grown up enough to provide content for the grown-up skater, and thank god for that.

In terms of text media, a cornucopia of books lay at the disposal of the eager skater who craves some meatier writing over the best-selling mags; you all may remember the review I wrote of Stalefish, and thankfully Sean Mortimer is but one of many skate-centric authors. For those of us, however, who can only budget so many books a year, there is always Juice Magazine, where the interviews are long, the stories are rich, and Steve Olson is, as always, a joy.

Thanks in no small part to Stacy Peralta, the skate world is also growing increasingly more rich in documentary videos. While this may invoke immediate imagery of Dogtown and Z-Boys, Rising Son, and Stoked, rest assured for all you skaters less than enthralled by the prospect of history that this bandwagon has been jumped on by contemporary companies as a welcome breath of fresh air to the typical relatively dialogue-free skate video, notably in Tent City, Drive, and The Final Flare. Regardless, though, the upcoming Bones Brigade documentary has most skaters probably about half as excited as I am about it, and when it does finally come out, I suggest you watch it immediately.

All told, I know that I've spent much of this blog pointing out what I consider to be some noticeable problems with the current state of skating, but I am proud that we have finally reached a point where there is a choice in the type of skate-related media we consume. at least, a better choice than "Thrasher or Transworld".

On a slightly happier note, today marks the day I get my cast off. It's been a surprisingly fast-moving seven weeks, and I had considered writing a sort of survival guide for anyone laid up with a bad break, except that there is little to know, except for the fact that you will do little more than watch web shows and gain a few extra pounds, so good luck to anyone in a similar situation. I know I'm still a ways off from actually skating again, much less at the level I was before my break, but I will toss out the occasional update as per my status.

To be perfectly honest, I had no idea when I started this post what exactly I planned on writing about. Typically, ideas for this blog come from my glancing a handful of skate news websites, maybe watching something that catches my eye, or a discussion with someone, with any of the three somehow going through a series of filters in my head, eventually leading me to some kind of conclusion I wish to ramble about that Monday or Thursday. This week, there was little to work with, or at least, little that my mind was able to form any kind of thoughts about that would carry for longer than maybe a paragraph. For instance, Go Skateboarding Day came and went on Tuesday... most skated, I didn't (for obvious reasons), end of story. As far as skate news, there didn't seem to be much to go on; perhaps it was the two months of not buying either Thrasher or Transworld, or the fact that there were no recent videos that really caught my eye...

...Alright, so the part about the videos isn't exactly true. In fact, in the last week I came across two videos that very much piqued my interest. So why then, you are likely asking, am I not blogging about said videos? Well, for one, I haven't given myself the time to watch them both in their entirety, and two, they are both interview-heavy skate documentaries.

As I find myself growing older, I can't help but note that creeping sense of disconnect between myself and the pulse of popular skating. Yes, I do make an effort to try and buy skate magazines every month, and yes I do peruse my handful of skate news sites daily, but the reality of the situation is that while, yes, the act of skateboarding may be the closest thing to the fountain of youth, even skateboarders mature to some degree. That being said, while I do still enjoy reading skate magazines and watching skate videos, it has gotten substantially harder to relate to the up-and-coming new-jacks of the industry; sixteen year old handrail hellions who, when interviewed, seem to have trouble using multisyllabic words, much less saying anything meaningful or engaging.

I can't be too hard on these kids, though. They're young, they lack life experience, and while it pains me to say it, most of them care little for being educated. The truth is, as a university alum and an older skater in general, I require substance in my reading and viewing material, and flipping through a series of six page interviews with maybe five hundred words of text simply feels sub-par.

Maybe it's my age, or maybe it's the fact that you can only read the same interviews and watch the same video parts so many times in one decade, but the important thing is that I, we, live in a day and age with choices. For so many years skateboard media was run by skaters, and skaters were kids; no one over twenty-five skated, because skating hadn't been around long enough. These days, the kids who ran the skate media of yesteryear have grown up enough to provide content for the grown-up skater, and thank god for that.

In terms of text media, a cornucopia of books lay at the disposal of the eager skater who craves some meatier writing over the best-selling mags; you all may remember the review I wrote of Stalefish, and thankfully Sean Mortimer is but one of many skate-centric authors. For those of us, however, who can only budget so many books a year, there is always Juice Magazine, where the interviews are long, the stories are rich, and Steve Olson is, as always, a joy.

Thanks in no small part to Stacy Peralta, the skate world is also growing increasingly more rich in documentary videos. While this may invoke immediate imagery of Dogtown and Z-Boys, Rising Son, and Stoked, rest assured for all you skaters less than enthralled by the prospect of history that this bandwagon has been jumped on by contemporary companies as a welcome breath of fresh air to the typical relatively dialogue-free skate video, notably in Tent City, Drive, and The Final Flare. Regardless, though, the upcoming Bones Brigade documentary has most skaters probably about half as excited as I am about it, and when it does finally come out, I suggest you watch it immediately.

All told, I know that I've spent much of this blog pointing out what I consider to be some noticeable problems with the current state of skating, but I am proud that we have finally reached a point where there is a choice in the type of skate-related media we consume. at least, a better choice than "Thrasher or Transworld".

|

| By the way, sorry there are no pictures in this post. Here's a picture of my surgical scar - hope that makes up for it... |

Labels:

ankle,

books,

documentary,

magazine,

RIP,

skateboarding,

video

Sunday, 19 June 2011

Parents, Birthdays, and the Rise of "Real Street"

First off, a belated Happy Father's Day to any readers who possess both a Y chromosome and at least one child, I hope you enjoyed your day.

Second, a very happy birthday to my girlfriend Deanna, who, aside from making the amazing new banner for the site, is just an amazing person in general. I love you, honey.

Now, on with the post:

It seems as though mainstream society has stopped trying with skateboarding...

...again.

It's the same as it ever was, and is about due. Anyone who has been alive and cognizant for the last twenty years or more can testify to the cyclical nature of skateboarding's popularity, which is usually symbolized by a gradual increase over the first half of a decade, followed by a three or four year span of mainstream frenzy, and a subsequent meteoric plummet into a kind of near-death torpor over the course of the next decade's inaugural months. It happened in the 60s, 70s, 80s, and 90s, although the advent of the internet, as well as skateboarding video games caused a funny thing to happen during the 2000s; that is to say, from 2000 to now, the cycle reversed.

Rather than suddenly plummeting back to Earth with enough force to drive it back underground, skateboarding experienced a solid wave of mainstream fame, and fortune up until around 2005 or so, when it seemed as though, rather than mainstream media dropping us like a dried up cash cow, as they are prone to do, skateboarding gradually backed away, leading us to today, in a society in which skateboarding is ever-present enough that skaters can make a decent living without the help of corporate non-skating puppet masters, leaving said puppeteers to look for moregullible pawns tacit investment opportunities. It seems to be working out alright for us skateboarders. Who wants to see skateboarding on TV every Saturday, anyway?

...Actually, I do kind of miss that part.

Now, I'll be the first to admit that my high-school years were filled with a supersaturation of "eXtreme!" television programming, and yes, much of it was unbelievably trying-too-hard cheesy, lumping skateboarding in with whatever fringe adventure-seeking activities execs could get their cocaine-dusted hands on, but there was, of course, the trade-off of knowing that every weekend from about April to October there was an excellent chance that there was some contest or another being broadcast on basic cable. To a teenage skate rat with no friends who skated themselves, this was a gift.

These days, it has become increasingly rare to see skateboarding on TV, so much so that I have my PVR set to record the Seattle stop of the Street League contest series. I can't remember the last time I watched a televised street contest, and to be perfectly honest, I don't know that I'll enjoy watching Street League as much as I enjoyed watching the X-Games, Gravity Games, Vans Triple Crown, and other such televised street contests of yore, largely due to the fact that I don't particularly care for the layout of modern street courses.

I understand that skateboarding changes, and that said change has to be facilitated. I also realize that course layouts such as those built for the Maloof and Street League contests are more enticing to the more "hardcore" street guys who would otherwise scoff at the idea of skating contests. This does not, however, mean that I think that said street courses are either the most entertaining, or the best venues upon which to have pro skaters compete. Rather, it is my belief that courses such as are used in the Maloof and Street League contests are quite the opposite.

In terms of the entertainment factor, these kinds of linear, spot-by-spot based street courses make for some of the least-fun-to-watch skateboarding. Does anybody know why ninety percent of a skater's video part is made up of tricks they landed? Because people watching the video don't want to watch forty-five minutes of ten guys trying one or two tricks apiece on a twelve-stair handrail. These courses are meant to replicate the experience of going to a street spot with a bunch of friends and sessioning, which is great if that's the kind of skating that you're into, and if you are the one skating. For the viewer, however, it becomes stale far too quickly, leaving one inclined to just wait for the video edits to come out online.

In terms of whether or not these are the best venues in which to have pro skaters compete? I would not only disagree, but would also offer that such street courses are unbalanced and detrimental to contemporary skateboarding. The funny thing about street contests from seven to ten years ago compared to today, is that the street courses then incorporated elements of all kinds of skateboarding. While this kind of skatepark-centric course design wasn't indicative of the tech-gnar gap and handrail craze during the time, it favoured well-rounded skateboarding. Conversely, the street courses of today, while catering to the small contingent Chris Coles, Greg Lutzkas, and Nyjah Houstons who still make their careers out of spending more time traveling to a spot than riding a skateboard at it, completely ignore the fact that there has been a shift in skateboarding towards the all-terrain rider, who would have fared far better in street contests of days passed than they would in the modern all-day best trick carcass-tosses.

Me, personally? I say bring back the pyramids, bring back, the quarter pipes, bring back the masonite, and bring back the non-linear layouts. A skateboard contest should be judged on how well you ride a skateboard, not how well you repeatedly jump down a set of stairs on one. Besides, at least watching the old courses get torn down wasn't this painful...

Oh, the humanity....

Second, a very happy birthday to my girlfriend Deanna, who, aside from making the amazing new banner for the site, is just an amazing person in general. I love you, honey.

Now, on with the post:

It seems as though mainstream society has stopped trying with skateboarding...

...again.

It's the same as it ever was, and is about due. Anyone who has been alive and cognizant for the last twenty years or more can testify to the cyclical nature of skateboarding's popularity, which is usually symbolized by a gradual increase over the first half of a decade, followed by a three or four year span of mainstream frenzy, and a subsequent meteoric plummet into a kind of near-death torpor over the course of the next decade's inaugural months. It happened in the 60s, 70s, 80s, and 90s, although the advent of the internet, as well as skateboarding video games caused a funny thing to happen during the 2000s; that is to say, from 2000 to now, the cycle reversed.

| |

| Another funny thing happened in the 2000s: The Osiris D3 |

Rather than suddenly plummeting back to Earth with enough force to drive it back underground, skateboarding experienced a solid wave of mainstream fame, and fortune up until around 2005 or so, when it seemed as though, rather than mainstream media dropping us like a dried up cash cow, as they are prone to do, skateboarding gradually backed away, leading us to today, in a society in which skateboarding is ever-present enough that skaters can make a decent living without the help of corporate non-skating puppet masters, leaving said puppeteers to look for more

...Actually, I do kind of miss that part.

|

| Okay, not all of it, but hear me out... |

Now, I'll be the first to admit that my high-school years were filled with a supersaturation of "eXtreme!" television programming, and yes, much of it was unbelievably trying-too-hard cheesy, lumping skateboarding in with whatever fringe adventure-seeking activities execs could get their cocaine-dusted hands on, but there was, of course, the trade-off of knowing that every weekend from about April to October there was an excellent chance that there was some contest or another being broadcast on basic cable. To a teenage skate rat with no friends who skated themselves, this was a gift.

| |

| Thankfully, I started skating in 2000, so the gift wasn't painted stupid colours. |

These days, it has become increasingly rare to see skateboarding on TV, so much so that I have my PVR set to record the Seattle stop of the Street League contest series. I can't remember the last time I watched a televised street contest, and to be perfectly honest, I don't know that I'll enjoy watching Street League as much as I enjoyed watching the X-Games, Gravity Games, Vans Triple Crown, and other such televised street contests of yore, largely due to the fact that I don't particularly care for the layout of modern street courses.

|

| Maloof 2011 Las Vegas |

I understand that skateboarding changes, and that said change has to be facilitated. I also realize that course layouts such as those built for the Maloof and Street League contests are more enticing to the more "hardcore" street guys who would otherwise scoff at the idea of skating contests. This does not, however, mean that I think that said street courses are either the most entertaining, or the best venues upon which to have pro skaters compete. Rather, it is my belief that courses such as are used in the Maloof and Street League contests are quite the opposite.

|

| 2011 Street League Seattle |

In terms of the entertainment factor, these kinds of linear, spot-by-spot based street courses make for some of the least-fun-to-watch skateboarding. Does anybody know why ninety percent of a skater's video part is made up of tricks they landed? Because people watching the video don't want to watch forty-five minutes of ten guys trying one or two tricks apiece on a twelve-stair handrail. These courses are meant to replicate the experience of going to a street spot with a bunch of friends and sessioning, which is great if that's the kind of skating that you're into, and if you are the one skating. For the viewer, however, it becomes stale far too quickly, leaving one inclined to just wait for the video edits to come out online.

|

| Slam City Jam 2001, Vancouver |

Me, personally? I say bring back the pyramids, bring back, the quarter pipes, bring back the masonite, and bring back the non-linear layouts. A skateboard contest should be judged on how well you ride a skateboard, not how well you repeatedly jump down a set of stairs on one. Besides, at least watching the old courses get torn down wasn't this painful...

Oh, the humanity....

Wednesday, 15 June 2011

I Don't Know Art, But I Know What I Ride

As mentioned on Monday, skateboarding attracts people from all walks, with all manner of interests outside of, yet often ultimately tied to skateboarding. A good portion of these people are visual artists. Given the abstract, often undefinable nature of both, the combination of the two is oftentimes inevitable, with examples of skateboarding crossing over into one's artwork becoming exceedingly more commonplace, amid everyone from professional artists who skate,

to professional skaters who make art, and everyone in-between.

Equally noticeable, of course, are examples of art crossing over into skateboarding; that is to say rather than a canvas being used to depict skateboarding, a skateboard can be used as a canvas. In cases such as this, it's not in any way uncommon to see one skater's art with another skater's name on it.

Mind you, an artist's work, is not limited to canvas, or seven-ply Canadian maple. Indeed, much like in skateboarding, many an artist will use whatever is at their disposal as a forum for their creative drive. Just as their skateboarding counterparts have different decks, trucks, and wheels for street spots, pools, vert ramps, and skateparks, visual artists may have various brushes, inks, paints, and spray cans for canvas, wood, paper, and yes, skateparks.

Now, for anyone who has been reading this blog with any kind of frequency, some of you may have caught on to the way I've been writing recently, and the most perceptive will be able to tell that the above preamble now segues into the topic I really intended to talk about in this post's outset. It was spurned by a recent call I got from my friend Brad, informing me that his heavily graffitied local bowl, the notorious Vanderhoof, was in the process of being coated in a layer of matte white paint: a layer of paint that he assumed would be re-covered with graffiti by the week's end. He subsequently sent me the following e-mail regarding the cover-up job:

"... it defiantly pisses me off of when bowls get graffitied... for reference I sent you the picture I sent on my phone.. I didn't take any photos [with my camera] though. But I did learn the boardslide fakie on the face wall."

Now, I understand, graffiti is inherently rebellious, skateboarding is inherently rebellious. Skaters want to hone their craft, graffiti artists want to hone their craft. I am, by no means, using this post as an attempt to admonish respectable graffiti artists for wanting a right to make art. On the other hand, however, is the case that while not everybody can ride a skateboard, anybody can buy a two-dollar can of black Krylon. The reason Vanderhoof is now coated in a layer of white is not because of the Autobots insignia carefully crafted on one wall of the hip, nor because of the clever "Vansderhoof" name-tag sprayed along the top of the tombstone's lip. Rather, Vanderhoof is likely looking more like Blanderhoof because some pubescent genius thought they were being clever by coating whatever free concrete was left with all manner of obscenities and genitalia, likely scrawled with about as much artistic skill as the neanderthal cave drawings scattered amid the prehistoric caves of modern France. Those who aren't offended by the content ought to be offended by the abhorrently poor "artwork".

Let this be a lesson to those of you out there who think that it is cool and clever to go to your local skatepark to spray paint an eight-year-old's representation of Mommy's last gynecological appointment, with a certain four-letter word describing the view: Bad graffiti is not cool or clever, it is a lame, juvenile, eyesore, and will ruin a potentially well-graffitied park for everybody. It could be repainted a dull white, or worse:

The alternative kind of speaks for itself...

Respect your local skatepark.

|

| Lance Mountain, Pro Skater who makes Art |

Equally noticeable, of course, are examples of art crossing over into skateboarding; that is to say rather than a canvas being used to depict skateboarding, a skateboard can be used as a canvas. In cases such as this, it's not in any way uncommon to see one skater's art with another skater's name on it.

Mind you, an artist's work, is not limited to canvas, or seven-ply Canadian maple. Indeed, much like in skateboarding, many an artist will use whatever is at their disposal as a forum for their creative drive. Just as their skateboarding counterparts have different decks, trucks, and wheels for street spots, pools, vert ramps, and skateparks, visual artists may have various brushes, inks, paints, and spray cans for canvas, wood, paper, and yes, skateparks.

|

| Shepard Fairey, Professional Artist who Skates |

Now, for anyone who has been reading this blog with any kind of frequency, some of you may have caught on to the way I've been writing recently, and the most perceptive will be able to tell that the above preamble now segues into the topic I really intended to talk about in this post's outset. It was spurned by a recent call I got from my friend Brad, informing me that his heavily graffitied local bowl, the notorious Vanderhoof, was in the process of being coated in a layer of matte white paint: a layer of paint that he assumed would be re-covered with graffiti by the week's end. He subsequently sent me the following e-mail regarding the cover-up job:

|

| Out with the old... |

Now, I understand, graffiti is inherently rebellious, skateboarding is inherently rebellious. Skaters want to hone their craft, graffiti artists want to hone their craft. I am, by no means, using this post as an attempt to admonish respectable graffiti artists for wanting a right to make art. On the other hand, however, is the case that while not everybody can ride a skateboard, anybody can buy a two-dollar can of black Krylon. The reason Vanderhoof is now coated in a layer of white is not because of the Autobots insignia carefully crafted on one wall of the hip, nor because of the clever "Vansderhoof" name-tag sprayed along the top of the tombstone's lip. Rather, Vanderhoof is likely looking more like Blanderhoof because some pubescent genius thought they were being clever by coating whatever free concrete was left with all manner of obscenities and genitalia, likely scrawled with about as much artistic skill as the neanderthal cave drawings scattered amid the prehistoric caves of modern France. Those who aren't offended by the content ought to be offended by the abhorrently poor "artwork".

Let this be a lesson to those of you out there who think that it is cool and clever to go to your local skatepark to spray paint an eight-year-old's representation of Mommy's last gynecological appointment, with a certain four-letter word describing the view: Bad graffiti is not cool or clever, it is a lame, juvenile, eyesore, and will ruin a potentially well-graffitied park for everybody. It could be repainted a dull white, or worse:

The alternative kind of speaks for itself...

Respect your local skatepark.

Monday, 13 June 2011

Authentic Simulation, or the Art of Couch Skating

As like many skaters, my interests reach further than simply the act of riding a skateboard. Some make art, some make music, some even ride motocross. I, myself, am a gamer.

Video game culture, and being a gamer, has a lot of parallels, I find, with skate culture. Both acts have been historically scoffed away as being child's play; something cast aside as soon as one gets a driver's license and a girlfriend. On that note, both have historically attracted the socially maladjusted: many a skater who went to high school in the 80s or early 90s will recount tales of how admitting you skated was a sure-fire way to detract attention from the opposite sex - a trait undoubtedly shared by the gamers of the same era. Both have an admittedly shameful history of male-dominated participation, bordering at times on misogyny.

Both have seen an increase in acceptance and casual participation in the last decade, and both have a collective of 'core curmudgeons who often rue that this is the case. So why am I talking about all of this? Well, because today I'm talking about what happens when these two things come together.

Maybe six months or so prior to starting Between Two Junkyards, I had mused about the idea of doing a video-review show all about skateboarding video games, of which there have been countless iterations, dating back as far as the 1986 classic 720 Degrees Arcade game, ported to the Atari 2600. While I could go on for months on end writing reviews of the rarely good, often bad, and occasionally ugly history of skateboarding video games, it ultimately boils down to the fact that, for the last quarter century, video game developers have been trying to emulate the act of skateboarding, without actually using a skateboard.

What really got my mind stirring on this topic was a recent binge I went on this weekend of video game webcomics. Due to my inherent need to be completely up-to-date on whatever webcomics I read, I came across this strip about Tony Hawk Ride. It brought up an interesting point: it a skateboarding game good because it's fun, or because it's realistic?

Well... kind of both.

In preparation for this blog, I talked to my girlfriend, who both skates and is an avid gamer, her thoughts on the matter:

"[Realism]...because [a more realistic game] helps you learn tricks: if it's easy and you can't fail what's the point? No video game should be like that. Where is the challenge?"

Now, I will defend the first handful of Tony Hawk games to the death - they were great games, and they did the best job possible at the time of capturing the act of skateboarding. Unfortunately, however, as the games progressed, they jumped the shark in an unforgivably huge way...

RIDE was meant, I suppose, to remedy this, as well as jump all over the Great Peripheral Bandwagon of the late 2000s. The aforementioned comic argued that the game was too real to be fun, though as a skater who actually tried it, it seemed more so that the game was simply trying too hard, and fell flat both in realism and fun. A valiant effort, Tony, but you and I both know that skateboarding is far more complex than the game's controls can account for.

Perhaps EA's Skate series is the closest modern technology has come to offering a fun, challenging, and accurate representation of skateboarding. I know I've spent countless hours playing the games, whose admittedly intuitive control scheme did offer me some assistance on my real-life fakie bigflips. Still, though, at the end of the day, no ammount of thumb-based training can compare to the feeling of actually getting out there and feeling the board under your feet.

Although it is a nice way to kill time on a rainy day.

Video game culture, and being a gamer, has a lot of parallels, I find, with skate culture. Both acts have been historically scoffed away as being child's play; something cast aside as soon as one gets a driver's license and a girlfriend. On that note, both have historically attracted the socially maladjusted: many a skater who went to high school in the 80s or early 90s will recount tales of how admitting you skated was a sure-fire way to detract attention from the opposite sex - a trait undoubtedly shared by the gamers of the same era. Both have an admittedly shameful history of male-dominated participation, bordering at times on misogyny.

Both have seen an increase in acceptance and casual participation in the last decade, and both have a collective of 'core curmudgeons who often rue that this is the case. So why am I talking about all of this? Well, because today I'm talking about what happens when these two things come together.

Maybe six months or so prior to starting Between Two Junkyards, I had mused about the idea of doing a video-review show all about skateboarding video games, of which there have been countless iterations, dating back as far as the 1986 classic 720 Degrees Arcade game, ported to the Atari 2600. While I could go on for months on end writing reviews of the rarely good, often bad, and occasionally ugly history of skateboarding video games, it ultimately boils down to the fact that, for the last quarter century, video game developers have been trying to emulate the act of skateboarding, without actually using a skateboard.

| |

| Yeah... This seems about right... |

Well... kind of both.

In preparation for this blog, I talked to my girlfriend, who both skates and is an avid gamer, her thoughts on the matter:

"[Realism]...because [a more realistic game] helps you learn tricks: if it's easy and you can't fail what's the point? No video game should be like that. Where is the challenge?"

Now, I will defend the first handful of Tony Hawk games to the death - they were great games, and they did the best job possible at the time of capturing the act of skateboarding. Unfortunately, however, as the games progressed, they jumped the shark in an unforgivably huge way...

|

| I heard Brian Herman just Franklin Grinded the Hollywood 16. |

Perhaps EA's Skate series is the closest modern technology has come to offering a fun, challenging, and accurate representation of skateboarding. I know I've spent countless hours playing the games, whose admittedly intuitive control scheme did offer me some assistance on my real-life fakie bigflips. Still, though, at the end of the day, no ammount of thumb-based training can compare to the feeling of actually getting out there and feeling the board under your feet.

Although it is a nice way to kill time on a rainy day.

Thursday, 9 June 2011

Skateboarding Is... June

First off, a quick word about this segment:

Back a few years ago, when I wrote the now-defunct Frontside Blog, I got to a point where I started doing a monthly feature, just a post about one thing in particular that I always thought really was an integral part of skateboarding, and of the culture of being a skateboarder. This post will serve as a resurrection of that old feature, and while I hope to, one day, revisit all my former topics, today I'm going to kick off the feature's relaunch with some brand new material - hope you all enjoy it.

Skateboarding is... Home-made ramps

They say that necessity is the mother of invention, and as anyone who has ever stepped on a skateboard can tell you, progression, and the honing of one's craft is as much a necessity as making sure you put on pants in the morning - even one day without doing so simply does not feel right. Skateboarders are creative by their very nature, and for those of us without a wealth of things to skate at our immediate disposal, the need to create does anything but subside, and that necessity, of course, leads to invention.

You would be hard-pressed to talk to a skater who has not, at one point, built some kind of object with the intention of skating it; from propping a spare piece of plywood up on a handful of bricks, to spending every other day for three straight weeks constructing a mini ramp with the perfect transition, I know I, personally, have done the former, the latter, and everything in-between.

The building process is, quite obviously, one of the key points of what makes a home-made obstacle home-made. Sadly, though, with a combination of a decrease in free time and an increased want for instant gratification, hordes of junky plastic contraptions litter the market billed often as "extreme sports ramps".

Call me old-fashioned, but I, for one, extoll the virtues of building something to skate as opposed to buying it, for a number of reasons.

1) If we are talking about a younger skater, say, under 16 or so, adult supervision should, in all good reason, be required, and for that matter, encouraged. A parent helping their child build something to skate will teach the child the value of working for something, as well as how to properly use power tools, which is always an asset. It will allow for some excellent parent-child bonding time, as even the simplest manual pad should, if well built, require at least an hour or two building time. Finally, and most importantly, it acts as a way of showing your child that you are genuinely interested in his or her activity of choice, and that you are willing to support their doing so.

2) If we are talking about older skaters, then for one thing, any attempt to use a cheap plastic launch ramp will likely result in little plastic shards within an hour, and $30 down the drain.

3) Customization: The ability to build something from scratch means that you can build it exactly the way you want it. A box can be a high and wide as you like, transitions can be cut as mellow or as steep as you want, you can tailor the obstacle to exactly your skill level and riding style. Be forewarned, though, that especially when talking about cutting transitions, make sure you know what you're doing beforehand. Thirteen foot transitions on a three foot quartepipe and you wind up with a flat bank with some coping, and four foot trannies on as big a mini and you have side-by-side Jersey Barriers (which is great if that's your thing). Cutting transitions is a delicate science, and one miscalculation can dash weeks of work on your first kickturn.

Here's how to do it right.

The best part is that customization of your home-made ramp doesn't always end at the building phase. Once all is said and done, this ramp is yours, so make it feel like yours: slap those spare stickers you have along the sides of it, use the top of it to practice your art skills, be it with a spray can or paint can, just do whatever you want to make it feel like home.

See an example at 1:09.

Everything associated with the home-made ramp comes back to creativity, and that is why it is so integral to the experience of being a skateboarder. I implore any of you who have never gotten your hands dirty with sawdust and a power drill, and even those of you who haven't done so in a while, go grab some wood, grab a buddy, grab a stereo, and grab hold of that creative spirit you embrace every time you step on your board, because among so many other things, skateboarding is... home-made ramps.

Back a few years ago, when I wrote the now-defunct Frontside Blog, I got to a point where I started doing a monthly feature, just a post about one thing in particular that I always thought really was an integral part of skateboarding, and of the culture of being a skateboarder. This post will serve as a resurrection of that old feature, and while I hope to, one day, revisit all my former topics, today I'm going to kick off the feature's relaunch with some brand new material - hope you all enjoy it.

Skateboarding is... Home-made ramps

| Yup, this is The Dream right here. |

They say that necessity is the mother of invention, and as anyone who has ever stepped on a skateboard can tell you, progression, and the honing of one's craft is as much a necessity as making sure you put on pants in the morning - even one day without doing so simply does not feel right. Skateboarders are creative by their very nature, and for those of us without a wealth of things to skate at our immediate disposal, the need to create does anything but subside, and that necessity, of course, leads to invention.

You would be hard-pressed to talk to a skater who has not, at one point, built some kind of object with the intention of skating it; from propping a spare piece of plywood up on a handful of bricks, to spending every other day for three straight weeks constructing a mini ramp with the perfect transition, I know I, personally, have done the former, the latter, and everything in-between.

The building process is, quite obviously, one of the key points of what makes a home-made obstacle home-made. Sadly, though, with a combination of a decrease in free time and an increased want for instant gratification, hordes of junky plastic contraptions litter the market billed often as "extreme sports ramps".

| |

| This is the equivalent of getting your kid a Fischer-Price Picnic Table to skate... |

1) If we are talking about a younger skater, say, under 16 or so, adult supervision should, in all good reason, be required, and for that matter, encouraged. A parent helping their child build something to skate will teach the child the value of working for something, as well as how to properly use power tools, which is always an asset. It will allow for some excellent parent-child bonding time, as even the simplest manual pad should, if well built, require at least an hour or two building time. Finally, and most importantly, it acts as a way of showing your child that you are genuinely interested in his or her activity of choice, and that you are willing to support their doing so.

2) If we are talking about older skaters, then for one thing, any attempt to use a cheap plastic launch ramp will likely result in little plastic shards within an hour, and $30 down the drain.

3) Customization: The ability to build something from scratch means that you can build it exactly the way you want it. A box can be a high and wide as you like, transitions can be cut as mellow or as steep as you want, you can tailor the obstacle to exactly your skill level and riding style. Be forewarned, though, that especially when talking about cutting transitions, make sure you know what you're doing beforehand. Thirteen foot transitions on a three foot quartepipe and you wind up with a flat bank with some coping, and four foot trannies on as big a mini and you have side-by-side Jersey Barriers (which is great if that's your thing). Cutting transitions is a delicate science, and one miscalculation can dash weeks of work on your first kickturn.

Here's how to do it right.

The best part is that customization of your home-made ramp doesn't always end at the building phase. Once all is said and done, this ramp is yours, so make it feel like yours: slap those spare stickers you have along the sides of it, use the top of it to practice your art skills, be it with a spray can or paint can, just do whatever you want to make it feel like home.

See an example at 1:09.

Everything associated with the home-made ramp comes back to creativity, and that is why it is so integral to the experience of being a skateboarder. I implore any of you who have never gotten your hands dirty with sawdust and a power drill, and even those of you who haven't done so in a while, go grab some wood, grab a buddy, grab a stereo, and grab hold of that creative spirit you embrace every time you step on your board, because among so many other things, skateboarding is... home-made ramps.

Monday, 6 June 2011

Oh, God, Back-to-Back Reviews? or Why Kristian Svitak Should Never Get Bent

I didn't want to post back-to-back reviews.

I can remember, back in 2004, there was a social networking site geared around skateboarding, called icelounge. The site was, more or less, a skate-centric myspace, where people could interact with other skaters, post photos and videos, and the big selling point (at least for me) was the ability to interact with the pros and companies who had accounts on the site, one of whom was Black Label skater Salman Agah.

I was never exactly a fan of Salman; I picked up skateboarding in 2000, and he was a little before my time. I was, however, a fan of the Label. Older tricks and a punk rock soundtrack? At eighteen years old, that was as good as it could get. Coming hot off the heels of the Blackout Video, I was itching to see more from guys like Kristian Svitak, Jason Adams, and Patrick Melcher, guys who skated the streets like they were backyard pools and it was 1983, and when Salman announced on his Icelounge account that he was taking over as Black Label Team Manager, I went onto his account and congratulated him, thinking that I'd be looking at the same old Label I loved, but with an established pro skater calling the shots.

In what seemed like one fell swoop, just about everything I liked about Black Label was gone. At the time I may have secretly blamed Slaman Agah for selling out; cutting away the old bones that used their hands and put down their feet in favour of jumping on the tight pants and handrails bandwagon that gripped the first half of the last decade like a vice. In hindsight, this probably wasn't the case, and although I was anticipating God Save the Label, I feel like the brand has lost much of the unique spark it held back in the early 2000's.

Melcher went to the UK's Death Skateboards: no one cared much, until recently when Richie Jackson made them a name to be heard over on this side of the pond.

Jason Adams went to Enjoi, and released what is, to this day, one of my favourite video parts, before heading back to Black Label for a time.

Svitak lied low for a couple of years, and then started 1031: People hated on it immensely, and expected it to fail within a year. For me, the company took that spark that the Label had in the first half of the last decade and ran with it. When Mike V left Element and got on Svitak's wheel company Landshark, for however brief a time, I was hoping he would wind up with 1031, which he did, in a way, with a limited-run guest model prior to his third-run return to Powell Peralta. When Jason Adams left the Label and announced that he would be riding under former teammate Svitak's Jack-o-Lantern banner, I was elated. When their new video Get Bent premiered online last Friday, I downloaded it instantly.

I didn't want to post back-to-back reviews.

The video is a testament to why 1031 has outlasted the naysayers, chock full of interesting, inspired skating from Cyril Jackson's opener straight through to Fritz Mead's ender, and even past the credits with Chad Knight's retrospective. The entire team really brings their best, bringing a perfect balance of skating that is at a high enough level to get you stoked, but creative and fun enough to make you want to go out at try it. It has a fast, hard soundtrack that gets your blood pumping, and is truly a memorable experience that anyone who rides a skateboard for the right reasons ought to witness.

I didn't want to post back-to-back reviews......

So watch it for yourself.

I can remember, back in 2004, there was a social networking site geared around skateboarding, called icelounge. The site was, more or less, a skate-centric myspace, where people could interact with other skaters, post photos and videos, and the big selling point (at least for me) was the ability to interact with the pros and companies who had accounts on the site, one of whom was Black Label skater Salman Agah.

I was never exactly a fan of Salman; I picked up skateboarding in 2000, and he was a little before my time. I was, however, a fan of the Label. Older tricks and a punk rock soundtrack? At eighteen years old, that was as good as it could get. Coming hot off the heels of the Blackout Video, I was itching to see more from guys like Kristian Svitak, Jason Adams, and Patrick Melcher, guys who skated the streets like they were backyard pools and it was 1983, and when Salman announced on his Icelounge account that he was taking over as Black Label Team Manager, I went onto his account and congratulated him, thinking that I'd be looking at the same old Label I loved, but with an established pro skater calling the shots.

In what seemed like one fell swoop, just about everything I liked about Black Label was gone. At the time I may have secretly blamed Slaman Agah for selling out; cutting away the old bones that used their hands and put down their feet in favour of jumping on the tight pants and handrails bandwagon that gripped the first half of the last decade like a vice. In hindsight, this probably wasn't the case, and although I was anticipating God Save the Label, I feel like the brand has lost much of the unique spark it held back in the early 2000's.

Melcher went to the UK's Death Skateboards: no one cared much, until recently when Richie Jackson made them a name to be heard over on this side of the pond.

Jason Adams went to Enjoi, and released what is, to this day, one of my favourite video parts, before heading back to Black Label for a time.

Svitak lied low for a couple of years, and then started 1031: People hated on it immensely, and expected it to fail within a year. For me, the company took that spark that the Label had in the first half of the last decade and ran with it. When Mike V left Element and got on Svitak's wheel company Landshark, for however brief a time, I was hoping he would wind up with 1031, which he did, in a way, with a limited-run guest model prior to his third-run return to Powell Peralta. When Jason Adams left the Label and announced that he would be riding under former teammate Svitak's Jack-o-Lantern banner, I was elated. When their new video Get Bent premiered online last Friday, I downloaded it instantly.

I didn't want to post back-to-back reviews.

The video is a testament to why 1031 has outlasted the naysayers, chock full of interesting, inspired skating from Cyril Jackson's opener straight through to Fritz Mead's ender, and even past the credits with Chad Knight's retrospective. The entire team really brings their best, bringing a perfect balance of skating that is at a high enough level to get you stoked, but creative and fun enough to make you want to go out at try it. It has a fast, hard soundtrack that gets your blood pumping, and is truly a memorable experience that anyone who rides a skateboard for the right reasons ought to witness.

I didn't want to post back-to-back reviews......

Loading the player ...

So watch it for yourself.

Thursday, 2 June 2011

My Thoughts on Others' Thoughts: A Review of "Stalefish"

Skateboarding, and skateboarders, owe an obscene debt of gratitude to Stacy Peralta. In his years as a professional skater, he may not have given us the frontside or backside airs, as did his peers Tony Alva and Tom Inoyue. At best, as a pro Peralta gave skateboarding backside 540 bertlemanns, frontside lipslides, and the knowledge that skateboarders, and skateboarding, could be marketed to the masses. As Peralta himself put it, it was behind the scenes where he truly flourished.

Perhaps it was the tutelage of Craig Stecyk, arguably one of the first skaters to become well-known and to make a career out of documenting skateboarding. Maybe it was Peralta's own ability to segue from having a career by skateboarding into having a career because of skateboarding. Maybe it's entirely ineffable. in the end, though, one cannot deny that Stacy Peralta has a unique ability to see where talent lies in a person, and to know how to guide said person toward cultivating that talent, honing it to the point of greatness.

The book Stalefish: Skateboard Culture from the Rejects Who Made it, was not written by Stacy Peralta, but rather, was penned by Sean Mortimer. One may be inclined to ask me why I just spent two paragraphs waxing poetic about Peralta as a means to preempt my review of a book that he did not author, which is valid. Mortimer, the author of Stalefish, as well as co-author of Tony Hawk and Rodney Mullen's autobiographies, rode for Powell Peralta as an amateur in the late '80s. As Mortimer once recounted in an interview, Peralta once overheard his musings as he shared an observation of a particular event. Peralta suggested Mortimer try his hand at writing, and for anyone who has read any of his works, this was yet another shining example of Peralta's innate eye for talent.

Stalefish the book is a few years old now, but is still, in my opinion, entirely worth reviewing, as I feel it to be somewhat underrated when cast in the gargantuan shadows of Occupation: Skateboarder and The Mutt. My girlfriend got me the book as a Christmas gift last year, and I am casually re-reading it now for what I swear is the tenth time.

The book is, more or less, a collection of anecdotes. The cast of contributing skaters is an astounding one that runs the gamut of skateboarding's past and present, as far back as Jim Fitzgerald and as contemporary as Chris Haslam, with a litany of others in-between: Russ Howell, Stacy Peralta, Steve Olson, Dave Hackett, Salba, Lance Mountain, Tony Hawk, Rodney Mullen, Tommy Guerrero, Kevin Harris, Mike Vallely, Bob Burnquist, Jamie Thomas, and Daewon Song round out the rest of the cast of characters, ensuring that no era or discipline is left unturned or unappreciated.

The stories themselves are not exactly autobiographical per se, as each chapter of the book focuses on a different aspect of skateboarding, and whomever has a tale or two to contribute as a means to chime in on the topic does so. In spite of the inherent looseness of the book's format, there is, understandably, some repetition in material for those who have read the Hawk and Mullen autobiographies. This is, of course, not necessarily a downside, which leads me to my next point.

What makes this book truly great, aside from instantly appealing to any and all skate-history nerds like myself, is that it is a collection of great stories being told by many of skateboarding's great storytellers. Anyone who has ever listened to Steve Olson say so much as three words will tell you that it is impossible to read anything he has written without hearing it in his voice, and that is not a bad thing. Most, if not all of the skaters interviewed for this book are so unique in their capacity to tell stories that one cannot help but hear their voices, be it Olson's cavalier slur, Mullen's excited mumble, or Mike V's intensity, every word truly jumps from the page, reverberating in the reader's head like the opening track of a favourite record.

While I cannot say enough great things about this book, no amount of my rambling will do it near as much justice as going out and giving it a read, and maybe later, nine more for good measure.

Stalefish is available for purchase here.

Perhaps it was the tutelage of Craig Stecyk, arguably one of the first skaters to become well-known and to make a career out of documenting skateboarding. Maybe it was Peralta's own ability to segue from having a career by skateboarding into having a career because of skateboarding. Maybe it's entirely ineffable. in the end, though, one cannot deny that Stacy Peralta has a unique ability to see where talent lies in a person, and to know how to guide said person toward cultivating that talent, honing it to the point of greatness.

The book Stalefish: Skateboard Culture from the Rejects Who Made it, was not written by Stacy Peralta, but rather, was penned by Sean Mortimer. One may be inclined to ask me why I just spent two paragraphs waxing poetic about Peralta as a means to preempt my review of a book that he did not author, which is valid. Mortimer, the author of Stalefish, as well as co-author of Tony Hawk and Rodney Mullen's autobiographies, rode for Powell Peralta as an amateur in the late '80s. As Mortimer once recounted in an interview, Peralta once overheard his musings as he shared an observation of a particular event. Peralta suggested Mortimer try his hand at writing, and for anyone who has read any of his works, this was yet another shining example of Peralta's innate eye for talent.

Stalefish the book is a few years old now, but is still, in my opinion, entirely worth reviewing, as I feel it to be somewhat underrated when cast in the gargantuan shadows of Occupation: Skateboarder and The Mutt. My girlfriend got me the book as a Christmas gift last year, and I am casually re-reading it now for what I swear is the tenth time.

The book is, more or less, a collection of anecdotes. The cast of contributing skaters is an astounding one that runs the gamut of skateboarding's past and present, as far back as Jim Fitzgerald and as contemporary as Chris Haslam, with a litany of others in-between: Russ Howell, Stacy Peralta, Steve Olson, Dave Hackett, Salba, Lance Mountain, Tony Hawk, Rodney Mullen, Tommy Guerrero, Kevin Harris, Mike Vallely, Bob Burnquist, Jamie Thomas, and Daewon Song round out the rest of the cast of characters, ensuring that no era or discipline is left unturned or unappreciated.

The stories themselves are not exactly autobiographical per se, as each chapter of the book focuses on a different aspect of skateboarding, and whomever has a tale or two to contribute as a means to chime in on the topic does so. In spite of the inherent looseness of the book's format, there is, understandably, some repetition in material for those who have read the Hawk and Mullen autobiographies. This is, of course, not necessarily a downside, which leads me to my next point.

What makes this book truly great, aside from instantly appealing to any and all skate-history nerds like myself, is that it is a collection of great stories being told by many of skateboarding's great storytellers. Anyone who has ever listened to Steve Olson say so much as three words will tell you that it is impossible to read anything he has written without hearing it in his voice, and that is not a bad thing. Most, if not all of the skaters interviewed for this book are so unique in their capacity to tell stories that one cannot help but hear their voices, be it Olson's cavalier slur, Mullen's excited mumble, or Mike V's intensity, every word truly jumps from the page, reverberating in the reader's head like the opening track of a favourite record.

While I cannot say enough great things about this book, no amount of my rambling will do it near as much justice as going out and giving it a read, and maybe later, nine more for good measure.

Stalefish is available for purchase here.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)